Regal House Publishing’s “That’s My Story” initiative seeks to introduce our writers and poets in a more unconventional way. We have supplied our authors with a significant number of unusual questions that pertain to the writing craft, and to various questions of a literary hue (some humorous, some a little twisted!), and others that we thought might be of interest to our audience. Each author selects and answers five, and of those five, Regal staff select two to three of the most delectable to be featured in our “That’s My Story” narrative. So each installment will feature a new author or poet, answering a unique set of questions that offer intriguing insight into their particular approach to the literary craft. While we had fun coming up with a slew of unorthodox questions, we also invite you, at the bottom of the page, to submit your own. What questions do you have that you would like Regal House authors and poets to answer? Let us know, and we will add them to our questionnaire.

Regal House Publishing’s “That’s My Story” initiative seeks to introduce our writers and poets in a more unconventional way. We have supplied our authors with a significant number of unusual questions that pertain to the writing craft, and to various questions of a literary hue (some humorous, some a little twisted!), and others that we thought might be of interest to our audience. Each author selects and answers five, and of those five, Regal staff select two to three of the most delectable to be featured in our “That’s My Story” narrative. So each installment will feature a new author or poet, answering a unique set of questions that offer intriguing insight into their particular approach to the literary craft. While we had fun coming up with a slew of unorthodox questions, we also invite you, at the bottom of the page, to submit your own. What questions do you have that you would like Regal House authors and poets to answer? Let us know, and we will add them to our questionnaire.

So join us, connect with us, and tell us about your own literary story.

Regal House Publishing begins our “That’s My Story” initiative with James Lawry, author of The Nudibranch Elegies and Anthropocene’s End, which will be released on August 24, 2018.

How do you think translation affects a story?

How do you think translation affects a story?

I love to study how languages intermingle and shed parts of themselves into each other as they, and we, evolve. Translations are especially hard and yet exciting as so many concepts have no precise translations. Gemuetlichkeit is translated as “coziness” or some such, but languages are so deep and complex, they contain so much more than literal meanings. This word also is suggestive of a sense of acceptance and comfort one finds in social acceptance, or can be evocative of atmosphere. Rhyming slang contains marvelous nuance, the meaning of which can be difficult to convey concisely within a novel but adds significant depth and texture. One might hear in London: “Don’t step on the pickles,” where the speaker wants you not to step on his newly scrubbed stairs, so he says pickles so you may substitute pears, rhyme it with stairs and get his message. I love language interactions! Poetry and plays and dialogue spring naturally from such word plays.

What’s next for me?

Everything. Old and gray and full of sleep at seventy-eight, each day is new. Even old stuff is new—an old piece becomes a new piece with any new reading. I always have multiple things in the hopper and work on each as the spirit moves. A sticky poem where the scansion and tropes don’t work, an old play finding a new twist, a new “if, then” experience, a new problem to be worked out, all can be variations for new themes.

False Bottom, a work on which I am currently engaged, deals with lives in the deep scattering layer of the oceans where many midwater animals rise and fall thousands of meters in a daily cycle tied to the sun cycle. I am examining, poetically, how the lives of these folks interact with each other while making their strange ascents and descents.

So an old man’s world is ever full. Each day he works and learns and imagines, and once in a great great while, when the baseball gods agree with all the others, he may send something off for others to see.

The Nudibranch Elegies and Anthropocene’s End made it to Regal House Publishing after trying many places, and may see the light of day come November—if the gods behave; each day is wait and see.

What do you read that people wouldn’t expect you to read?

Everything. Math, science, old authors, new authors, history, engineering, especially books and papers from other countries, languages and times. Books filled with ideas such as Calvino’s Invisible Cities. Kawabata’s novels, Robert Musil’s Man Without Qualities, and for me especially Ford Maddox Ford’s Parade’s End and the Good Soldier, all help me cope with today’s world.

What’s your process for writing: do you outline, create flow charts, fill out index cards, or just start and see where you end up? Do you use the same process every time?

Ideas come and go. Some stay and grow, and a few become iconic. Ones that remain do so for a reason. Find the reason. In mulling, new ideas come and attach themselves to others over time.

This part of the process can never be forced. What comes is what comes of its own will, often after periods of rest. The newly becoming idea swirls around and grows strange over and over, but parts lose themselves and others stay. Those that stay become catalysts for new pieces.

A character of mine, Moabit Bird, says it thus: “As long as I stay ignorant and don’t judge, I can learn new things when looking out into the world. I don’t know where I’m going, what I’m going to see or meet, so I must open myself. Then I may learn what reality is.”

___________________________________________

Be a part of our ongoing “That’s My Story” initiative. Do you have questions you would like featured? Want to share your own literary story? We would love to hear from you!

The modern world provides us with countless conveniences. Almost anything we could want is available for purchase within seconds, at any moment. Amazon can deliver a package to our house within days for free, and this convenience is exemplified by book deliveries, its flagship service. So why then do we still go to book stores to buy books? This simple answer is that we don’t; we go for the experience. The more complicated answer involves our relationship with books and our emotional responses to seeing them, browsing them, the wholly deliberate de-commodification we enact by treating books as something slightly more sacred than most of the other objects we buy. Bookstores evoke a complex web of interconnected desires, sensations, and visceral satisfactions, all of which can be more or less articulated as the smell of books. As services like Amazon out-supply big-name stores like Borders and Barnes & Noble with its unlimited capacity and as sleek e-readers pose as practical upgrades to thousand-page tomes, an independent bookstore like Flyleaf Books continues to thrive because it is an important member of the community for which simple convenience could never substitute.

The modern world provides us with countless conveniences. Almost anything we could want is available for purchase within seconds, at any moment. Amazon can deliver a package to our house within days for free, and this convenience is exemplified by book deliveries, its flagship service. So why then do we still go to book stores to buy books? This simple answer is that we don’t; we go for the experience. The more complicated answer involves our relationship with books and our emotional responses to seeing them, browsing them, the wholly deliberate de-commodification we enact by treating books as something slightly more sacred than most of the other objects we buy. Bookstores evoke a complex web of interconnected desires, sensations, and visceral satisfactions, all of which can be more or less articulated as the smell of books. As services like Amazon out-supply big-name stores like Borders and Barnes & Noble with its unlimited capacity and as sleek e-readers pose as practical upgrades to thousand-page tomes, an independent bookstore like Flyleaf Books continues to thrive because it is an important member of the community for which simple convenience could never substitute. The interior almost seems designed to facilitate a sense of discovery and opportunity. After meandering through the front area, browsing the newest releases and staff favorites, the staff-curated poetry section and various fiction and non-fiction sections, you are inevitably drawn towards the back of the store to discover the—again, curated—children’s section. The space is semi-contained by half- and full-sized bookshelves and resembles a play area. To the other side, an entrance opens up into a large, spacious room containing the used books section. This space serves as a reflection of the front, with bookshelves lining the walls and tables set up in the middle. This is also the space where the community engages itself in the events hosted by the store.

The interior almost seems designed to facilitate a sense of discovery and opportunity. After meandering through the front area, browsing the newest releases and staff favorites, the staff-curated poetry section and various fiction and non-fiction sections, you are inevitably drawn towards the back of the store to discover the—again, curated—children’s section. The space is semi-contained by half- and full-sized bookshelves and resembles a play area. To the other side, an entrance opens up into a large, spacious room containing the used books section. This space serves as a reflection of the front, with bookshelves lining the walls and tables set up in the middle. This is also the space where the community engages itself in the events hosted by the store. Flyleaf is clearly managed by people who care about what they do. Over the course of interviewing her, Jamie stopped several times to personally make sure that people in the store had help if needed. When speaking about the store, she mentioned that, growing up in Chapel Hill, she had always wanted someone to open up the kind of bookstore Flyleaf has become. One can’t help but think of Toni Morrison’s advice to write the book you want to read; the same can be said of the stores that sell them. It certainly isn’t the largest bookstore in the area, but with its carefully managed selection, that hardly matters. Each section is constantly curated, and Jamie joked that five different people touch each book before it makes it to the shelf. When browsing the selections, that level of care is obvious. Jamie worked to find the right mix of people to help her manage the store and noted how happy she is with the staff group and culture.

Flyleaf is clearly managed by people who care about what they do. Over the course of interviewing her, Jamie stopped several times to personally make sure that people in the store had help if needed. When speaking about the store, she mentioned that, growing up in Chapel Hill, she had always wanted someone to open up the kind of bookstore Flyleaf has become. One can’t help but think of Toni Morrison’s advice to write the book you want to read; the same can be said of the stores that sell them. It certainly isn’t the largest bookstore in the area, but with its carefully managed selection, that hardly matters. Each section is constantly curated, and Jamie joked that five different people touch each book before it makes it to the shelf. When browsing the selections, that level of care is obvious. Jamie worked to find the right mix of people to help her manage the store and noted how happy she is with the staff group and culture.

You move into a new house, and of course it’s a hell of a lot of work. We’ve been pulling fourteen-hour days, hauling boxes till our arms and legs ache. And you start setting things up, just so. This goes here—should we put that over there? A seemingly endless number of objects to be placed, to be positioned as the perfect slaves they are, never moving unless we bid them. And you start learning the little peculiarities of the place—the way you have to pull just so to get the shower to work—how the front door sticks a bit. Even the sounds of it, a kind of minor encyclopedia: the kitchen tile you keep stepping on, that makes an odd squelching noise—the way china rattles in the hutch when someone walks past.

You move into a new house, and of course it’s a hell of a lot of work. We’ve been pulling fourteen-hour days, hauling boxes till our arms and legs ache. And you start setting things up, just so. This goes here—should we put that over there? A seemingly endless number of objects to be placed, to be positioned as the perfect slaves they are, never moving unless we bid them. And you start learning the little peculiarities of the place—the way you have to pull just so to get the shower to work—how the front door sticks a bit. Even the sounds of it, a kind of minor encyclopedia: the kitchen tile you keep stepping on, that makes an odd squelching noise—the way china rattles in the hutch when someone walks past. I worried for days, unaware of it, that there were no mockingbirds here. So many in our old neighborhood—and just three miles away! The world alive with them in May and June, their songs filling me whether I listened or not. Then I heard one, here, from the branches of the Modesto ash in our front yard. Fool, I told myself—you just happened to move in early July, the season shifts, they stop singing then. Mates are already won, sex on hidden branches has filled the world with a different, silent kind of song—eggs are growing in feathered bodies, nests being built. They’re here too. Of course.

I worried for days, unaware of it, that there were no mockingbirds here. So many in our old neighborhood—and just three miles away! The world alive with them in May and June, their songs filling me whether I listened or not. Then I heard one, here, from the branches of the Modesto ash in our front yard. Fool, I told myself—you just happened to move in early July, the season shifts, they stop singing then. Mates are already won, sex on hidden branches has filled the world with a different, silent kind of song—eggs are growing in feathered bodies, nests being built. They’re here too. Of course. In the middle of our big moving day, sweating and dirt-smudged, she and I paused at twilight to glimpse the new crescent through vines and trees in the backyard. Nothing made us feel more at home.

In the middle of our big moving day, sweating and dirt-smudged, she and I paused at twilight to glimpse the new crescent through vines and trees in the backyard. Nothing made us feel more at home.

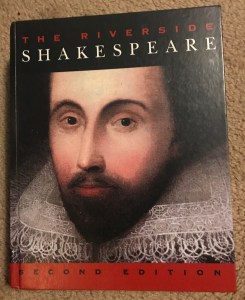

We could pause here to debate whether Hal is a clever politician or a rotten blackguard, if his companions deserve such a reversal, whether Hal is reluctant to do what he knows must be done or gleefully anticipating pulling the rug out from under Poins, Bardo, and especially Falstaff (“No, my good lord; banish Peto, banish Bardolph, banish Poins: but for sweet Jack Falstaff, kind Jack Falstaff, true Jack Falstaff, valiant Jack Falstaff, and therefore more valiant, being, as he is, old Jack Falstaff, banish not him thy Harry’s company, banish not him thy Harry’s company: banish plump Jack, and banish all the world”), but if anyone wants to have that discussion, let’s save it for the comments.

We could pause here to debate whether Hal is a clever politician or a rotten blackguard, if his companions deserve such a reversal, whether Hal is reluctant to do what he knows must be done or gleefully anticipating pulling the rug out from under Poins, Bardo, and especially Falstaff (“No, my good lord; banish Peto, banish Bardolph, banish Poins: but for sweet Jack Falstaff, kind Jack Falstaff, true Jack Falstaff, valiant Jack Falstaff, and therefore more valiant, being, as he is, old Jack Falstaff, banish not him thy Harry’s company, banish not him thy Harry’s company: banish plump Jack, and banish all the world”), but if anyone wants to have that discussion, let’s save it for the comments.

Ruth Feiertag is the senior editor of Regal House Publishing. She holds a B.A. from the University of California Santa Cruz and an M.A. from the University of Colorado at Boulder. She finds Medieval and Renaissance literature (mostly poetry and drama) endlessly fascinating, and anyone who wants to be treated to a long monologue should ask her about bastards from the Middle Ages through the Early Modern period. Ruth is the founding editor of

Ruth Feiertag is the senior editor of Regal House Publishing. She holds a B.A. from the University of California Santa Cruz and an M.A. from the University of Colorado at Boulder. She finds Medieval and Renaissance literature (mostly poetry and drama) endlessly fascinating, and anyone who wants to be treated to a long monologue should ask her about bastards from the Middle Ages through the Early Modern period. Ruth is the founding editor of  Like so many others, I had moved to New York City with a dream to write, to be at the center of things and pay attention. But such a reality, even in the service of a great dream, is a hard and often lonely one. I knew it wouldn’t be an easy move to make, but I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t harder than I guessed it would be. I was out of my element and struggling to find my place. I knew very few people. To say that I was overwhelmed and scared on a daily basis would be an understatement.

Like so many others, I had moved to New York City with a dream to write, to be at the center of things and pay attention. But such a reality, even in the service of a great dream, is a hard and often lonely one. I knew it wouldn’t be an easy move to make, but I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t harder than I guessed it would be. I was out of my element and struggling to find my place. I knew very few people. To say that I was overwhelmed and scared on a daily basis would be an understatement. I had an appointment. I was set to interview

I had an appointment. I was set to interview

At this point in our conversation, Carol stopped and looked far off. I followed her line of sight. She was looking out the window, at the streams of autumnal light. Whatever she said next would be carefully considered. She took a deep breath.

At this point in our conversation, Carol stopped and looked far off. I followed her line of sight. She was looking out the window, at the streams of autumnal light. Whatever she said next would be carefully considered. She took a deep breath.

Our conversation shifted to New York City as a place, as an inspirational, larger-than-life refuge for writers and musicians and artists. I asked Carol, as a devoted New Yorker, if she had any advice for visitors of the city. If they only had one day to spend here, what should they do?

Our conversation shifted to New York City as a place, as an inspirational, larger-than-life refuge for writers and musicians and artists. I asked Carol, as a devoted New Yorker, if she had any advice for visitors of the city. If they only had one day to spend here, what should they do? Preferring to write in private was yet another similarity we had. Like Carol, I write best at my desk, looking out at the George Washington Bridge and the Hudson River. Across the river sits New Jersey. The view, the cool breeze, even the sporadic beep-beeps from cars below culminate in an almost dreamlike setting to write. New York City: right outside my window.

Preferring to write in private was yet another similarity we had. Like Carol, I write best at my desk, looking out at the George Washington Bridge and the Hudson River. Across the river sits New Jersey. The view, the cool breeze, even the sporadic beep-beeps from cars below culminate in an almost dreamlike setting to write. New York City: right outside my window. That’s the thing about New York. It’s wild. Every kind of person is represented, walking to some meeting, some friend, some restaurant. It is a place of variety and stimulating diversity, where there is always a million-and-one things to do at any given time. Sit in Washington Square Park and watch the people go by. You won’t see such range anywhere else. And that energy? That New York City energy? That’s there, too. We have energy in spades.

That’s the thing about New York. It’s wild. Every kind of person is represented, walking to some meeting, some friend, some restaurant. It is a place of variety and stimulating diversity, where there is always a million-and-one things to do at any given time. Sit in Washington Square Park and watch the people go by. You won’t see such range anywhere else. And that energy? That New York City energy? That’s there, too. We have energy in spades.

At this we laughed. I told her that I started writing as an escape. The town I grew up in was small and pretty dull. I needed to lie and tell stories to make things interesting. I shared my theory: all writers are liars. We have to be, to some extent. We have to lie to get to the heart of the matter. We have to stretch boundaries and make impossible things possible to learn how to tell the truth.

At this we laughed. I told her that I started writing as an escape. The town I grew up in was small and pretty dull. I needed to lie and tell stories to make things interesting. I shared my theory: all writers are liars. We have to be, to some extent. We have to lie to get to the heart of the matter. We have to stretch boundaries and make impossible things possible to learn how to tell the truth. I have always loved reading and creating, with words, with paint and pencils, from joining a Creative Writing class as a child – as an asthmatic and more than a little uncoordinated, team sports were never my forte – to studying art and then writing at university. Since childhood, when I realised that someone had created the book I held in my hand, I have wanted to write. To create. Perhaps it was reading Little Women and wanting so fiercely for Jo to succeed, to be Jo, or alternatively her sisters and enter the Marsh household. Perhaps it was Alice in Wonderland and wanting to throw myself down that rabbit hole. Books were a perfect escape when I was indoors with another bout of bronchitis. They gave me the world. From those tame beginnings to discovering books could not only captivate and inspire me, but thrill me and scare me, keeping me up at night reading under the blankets with a torch. Books introduced me and immersed me in new worlds.

I have always loved reading and creating, with words, with paint and pencils, from joining a Creative Writing class as a child – as an asthmatic and more than a little uncoordinated, team sports were never my forte – to studying art and then writing at university. Since childhood, when I realised that someone had created the book I held in my hand, I have wanted to write. To create. Perhaps it was reading Little Women and wanting so fiercely for Jo to succeed, to be Jo, or alternatively her sisters and enter the Marsh household. Perhaps it was Alice in Wonderland and wanting to throw myself down that rabbit hole. Books were a perfect escape when I was indoors with another bout of bronchitis. They gave me the world. From those tame beginnings to discovering books could not only captivate and inspire me, but thrill me and scare me, keeping me up at night reading under the blankets with a torch. Books introduced me and immersed me in new worlds.

I was concerned about and for my characters. I needed to ensure that Arthur in particular had moments, however fleeting, when he was ‘human’, and that Ellie, despite her circumstances, not be passive. I found myself going off in tangents in early drafts with minor characters and subplots but judicious readers and editing brought the focus back to Ellie and Arthur, and the confines of restricted world they inhabit.

I was concerned about and for my characters. I needed to ensure that Arthur in particular had moments, however fleeting, when he was ‘human’, and that Ellie, despite her circumstances, not be passive. I found myself going off in tangents in early drafts with minor characters and subplots but judicious readers and editing brought the focus back to Ellie and Arthur, and the confines of restricted world they inhabit.

Halfway to Tallulah Falls, my son spills his entire bottle of Gatorade into his lap. “Um, Mommmmmay?” He says in a tentative, keening voice, emphasis on the last syllable, the way he always does, adding a frantic edge to what is not really an emergency. “I spilled my drink.” I sigh, tilting back my own water bottle and taking an eager gulp. Thankfully I have leather seats, though we didn’t bring any spare pants and I have no idea how he’s going to hike down a mountain with his butt soaked through.

Halfway to Tallulah Falls, my son spills his entire bottle of Gatorade into his lap. “Um, Mommmmmay?” He says in a tentative, keening voice, emphasis on the last syllable, the way he always does, adding a frantic edge to what is not really an emergency. “I spilled my drink.” I sigh, tilting back my own water bottle and taking an eager gulp. Thankfully I have leather seats, though we didn’t bring any spare pants and I have no idea how he’s going to hike down a mountain with his butt soaked through. Up the mountain, we stop in the gift shop and buy the kid a pair of leggings and a piece of rock candy in his newest favorite color; cyan. On the way outside, he stops to study a taxidermied fox. We visit the museum exhibit, and I point out the boxcars, the butter churn, the crisp, thin white dresses with their square collars; all relics from a time gone by, with lessons to be gleaned. He nods, but isn’t really paying attention. What use does an eight year old have for sack dresses? He wants to get outside, into the air, to touch the stone and bark, to walk the paths, to hear the delicious crunch of the leaves beneath his feet, and I don’t blame him.

Up the mountain, we stop in the gift shop and buy the kid a pair of leggings and a piece of rock candy in his newest favorite color; cyan. On the way outside, he stops to study a taxidermied fox. We visit the museum exhibit, and I point out the boxcars, the butter churn, the crisp, thin white dresses with their square collars; all relics from a time gone by, with lessons to be gleaned. He nods, but isn’t really paying attention. What use does an eight year old have for sack dresses? He wants to get outside, into the air, to touch the stone and bark, to walk the paths, to hear the delicious crunch of the leaves beneath his feet, and I don’t blame him. When he was two he wandered off while I was putting his carseat in – I turned and he had vanished. Those ten minutes felt like hours, and when we found him, he was wandering out of the woods – the forests in Oconee County are heady and thick with skinny, gray-brown pine trees, tall and imposing, but full of a gentle kind of calm, as though benevolent ghosts might pass their days there in a cocoon of sweet silence – with our little beagle in tow, humming a little tune as his fat, toddler hands grazed each tree, oblivious and full of joy. He is a natural wanderer, my kid – and while it isn’t always ideal, and are sometimes stressful, these wanderings – I always understand them. I always understand him. In so many ways just like me, but in others so wholly different, so pure and clear-eyed and awake. I feel I know him better than I’ve ever known myself. He is a natural wanderer, fluent in the woods, a real-life tree hugger. He has always felt at home there in the silence of the woods, a place where he is heard and understood, nurtured and adored.

When he was two he wandered off while I was putting his carseat in – I turned and he had vanished. Those ten minutes felt like hours, and when we found him, he was wandering out of the woods – the forests in Oconee County are heady and thick with skinny, gray-brown pine trees, tall and imposing, but full of a gentle kind of calm, as though benevolent ghosts might pass their days there in a cocoon of sweet silence – with our little beagle in tow, humming a little tune as his fat, toddler hands grazed each tree, oblivious and full of joy. He is a natural wanderer, my kid – and while it isn’t always ideal, and are sometimes stressful, these wanderings – I always understand them. I always understand him. In so many ways just like me, but in others so wholly different, so pure and clear-eyed and awake. I feel I know him better than I’ve ever known myself. He is a natural wanderer, fluent in the woods, a real-life tree hugger. He has always felt at home there in the silence of the woods, a place where he is heard and understood, nurtured and adored. When he graduates high school, I plan to take him on a hike through the Appalachian Trail. I haven’t told him yet, but it’s a secret dream. It seems poignant, appropriate. I can picture him, sweaty blonde hair, cheeks flushed with red in the cool air, panting with exertion, a heavy backpack weighing down wide shoulders. Undoubtedly he’ll have spilled his Gatorade on his pants, or tripped and skinned a knee, but there will be joy.

When he graduates high school, I plan to take him on a hike through the Appalachian Trail. I haven’t told him yet, but it’s a secret dream. It seems poignant, appropriate. I can picture him, sweaty blonde hair, cheeks flushed with red in the cool air, panting with exertion, a heavy backpack weighing down wide shoulders. Undoubtedly he’ll have spilled his Gatorade on his pants, or tripped and skinned a knee, but there will be joy.